I wrote an article in reaction to the so-called Gospel of Judas. Philippine Daily Inquirer (Sunday 09 April 2006) published it front page. Here's an unedited version of that.

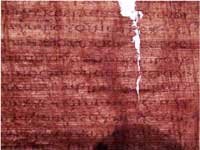

The controversial "Gospel of Judas" is soon to be made available to the public. The National Geographic Society has announced its intention to publish later this month an English translation of a 31-page ancient manuscript written in Coptic language. Judas is a "saint" in this writing, as some press releases have insinuated. The publication is timely. It is Holy Week, days when we Christians "weep" for Jesus and scorn Judas. Likewise, the publication is opportune commercially as it rides high on the economic success of The Da Vinci Code and the soon-to-released movie based on it. The novel claims that the Vatican

The publication of this Coptic manuscript, if authentic, will give us a text of what we know only from secondary sources, from the reports of the early Christian writers on a certain Gospel of Judas. Also, it will shed light on how early Christians, at least from the so-called "Gnostics" understood Judas. Coptic was the indigenous language of Egypt Egypt

In the 2nd century A.D., discrete religious movements began to challenge Christianity, especially in Egypt village of Nag Hammadi Vatican

Among the Church Fathers, Irenaeus of Lyons (ca. 130-200) was the earliest reporter to inform us of the challenges of the Gnostics. In his writing, Against Heresies he mentioned a sect calling themselves the Cainites (followers of Cain) and possessing a book they call the Gospel of Judas. Another writer, Epiphanius of Salamis (ca. 310-403) described the Cainites as boasting of being relatives of Cain, the Sodomites, Esau, and Korah. Those who know their Bible well will understand that these characters are biblical villains. And so naturally the Cainites admired the greatest villain of all, Judas Iscariot. Epiphanius writes: "They consider him [Judas] their kinsman and count him among those possessing the highest knowledge, and so they also carry about a short writing in his name which they call the Gospel of Judas." In that culture, to call someone kinsfolk is to be a follower of that person, one reason why Jesus called his disciples "brothers".

If Judas achieved such heavenly knowledge, a Gnostic Nirvana so to say, why did he betray Jesus? Epiphanius tells us of two reasons given by this group: (1) Judas knew, remember he had the knowledge, that Christ was wicked because he "wanted to distort what pertains to the Law." Here one must remember that Jesus' teachings often came in conflict with the Jewish understanding of the Law of Moses. (2) Judas knew that the power of the "archons" (these are naughty and lesser deities in Gnostic cosmology) would be drained if Christ were to be crucified. So Judas "bent every effort to betray him, thereby accomplishing a good work for our salvation." The Cainites argued that Christians in fact should "admire and praise" Judas, "because through him the salvation of the cross was prepared for us and the revelation of things above occasioned by it."

In short, in the eyes of this group, Judas helped Jesus to save humanity when he betrayed his master. He therefore faired better than the rest of the disciples who did not understand that Jesus must suffer and die.

We can raise two questions on the logic of this Gnostic group. If they were indeed sincere of preserving the Law of Moses, why did they claim to be followers of Korah (leader of the first unsuccessful "people power" against Moses and Aaron; see Numbers 16:1-50)? Second, if Judas had the knowledge of Jesus' fate, why did he not have the knowledge of his own fate--his attempt to return the money to the authorities, his remorse, and eventual suicide? Whatever we understand today of the psychology of suicide, it was the most shameful death in the world. It is well known that Gnostics emphasized knowledge over moral actions.

Of course, we are reading the polemics of the Church Fathers who were refuting the Gnostics at the time. Their description, in a way, was "colored" by their intent. That's why the forthcoming publication of a copy of the Gospel of Judas can offer us direct evidence of what Gnostics might have thought of Judas or the stories of him they might have told.

In a positive sense, the story of Judas will allow us to rethink the problem of God and evil in the world (technically called "theodicy"). Since what Judas did was part of God's plan, does God then intend evil in the world? Dear to the Gnostics is the idea that God created a disordered and chaotic world. We don't even have to be a Gnostic to realize that the world at times is flawed. How else can we explain this but to say that God is responsible for this? That's why the Gnostics adored the villains like Judas. They were the epitomes of a disordered world. But the issue they raised is in no way fresh.

Around 4,000 years ago, in the ancient Near East, there was already literature containing laments of individuals over the seeming injustice on the part of God. In the Bible, we read a long debate over this issue in the Book of Job--God allowing and tolerating "the adversary" (hassatan in Hebrew) to destroy a very good person like Job. Such experience is universal. Our local papers reported once of a young man, losing all that he had including his family in the Guinsaugon tragedy, who broke down in a mass, lamenting: "I don't believe in God anymore. Why did He take away our loved ones, the old and the young?" For us Christians, evil is a reality as well as a mystery with which we have to reckon, finding its climax and answering Jesus' passion and death.

Another controversy that could come out from reading the Gospel of Judas is the question of God's mercy and forgiveness. If God were indeed merciful, did he forgive Judas? Traditionally, many have thought that Judas is probably in hell, because of Jesus' severe indictment of Judas: "It would be better for that man if he had never been born," as he says in Mark 14:21. But these words do not tell us of the fate of Judas. Jesus' words were more of a lament rather than a legal sentence. That explains why Job and Jeremiah lamented, out of their present sufferings, better to have not been born (Job 3:11; Jer 20:18).

Let us take two scenes from the Passion Narrative to illustrate Jesus' compassionate attitude toward Judas. First, during the Last Supper, in the account of the earliest Gospel, the Gospel of Mark, Jesus predicted that the one who was eating with him was going to betray him. Jesus did not identify who would be the traitor. In the version of Matthew, Judas spoke: "Is it I, Lord?" In Greek, this rhetorical question should mean, "Surely, not I Lord?" expecting a "No" for an answer. After Judas had asked a second time, Jesus replied, "You have said so". It was an ambiguous answer. The rest of the disciples understood that Jesus was not referring to Judas since they did not react against him. But the Gospel writer intended his readers to understand that Jesus knew somehow of Judas' evil plan. At that point, Judas could have retracted.

Another familiar scene is Judas' kiss at the Mount of Olives . Luke has this account: "He [Judas] approached Jesus to kiss him, but Jesus said to him, 'Judas, is it with a kiss that you are betraying the Son of Man?'" Judas was about to kiss Jesus but Jesus warned him, at the very last moment, to refrain from the evil act. Another chance was offered to retract.

In short, Jesus was giving all the chances for Judas not to commit such treachery, and that Judas was responsible for his actions.

In a similar spirit, St. Vincent Ferrer (1350-1419), an influential Dominican preacher, said in a sermon in 1391:

Judas who betrayed and sold the Master after the cruciflixion was overwhelmed by a genuine and saving sense of remorse and tried with all his might to draw close to Christ m order to apologize for his betrayal and sale. But since Jesus was accompanied by such a large crowd of people on the way to the mount of Calvary , it was impossible for Judas to come to him and so he said to himself: Since I cannot get to the feet of the master, I will approach him in my spirit at least and humbly ask him for forgiveness. He actually did that and as he took the rope and hanged himself his soul rushed to Christ on Calvary 's mount, asked for forgiveness and received it fully from Christ. He went up to heaven with him and so his soul enjoys salvation along with all elect.

Nonetheless, an evil act is always an evil act no matter what the result may be. The end does not justify the means, so we say. Early Christian writers saw to it that Judas' action was not worth emulating. He was motivated by greed (Matt 26:15), by Satan (Luke 22:3), and by Satan plus a habit of stealing (John 13:2; 12:6). Thus they stressed Judas' violent death, whether through a suicide as Matthew 27:5 informed us, or as Luke recounted in the Acts of the Apostles: "Falling headlong, he [Judas] burst open in the middle and all his bowels gushed out." More gruesome is the report of Papias in the early 2nd century A.D.:

His flesh swelled so much that he could not pass where a cart could easily. His eyelids swelled so much that he could not see any light at all, and his eyes could not be seen even with a doctor's instruments, because they had sunken so far from the surface of his face. His genitals were more enlarged and unsightly than any other deformity, while blood and worms flowed from all over his body, necessarily doing great harm just by themselves. After many such tortures and punishments, he died on his own property, and that on account of the stench the place is desolate and uninhabited even until now, and that today no one can go through that place without stopping up his nose with his hands, because the stench of his flesh spread out over the land so much.

Even for us Filipinos, we do not tolerate Judas' actions. That's why his image is absent in the procession during Good Friday; in the jeepneys, in play on his name, the cheater is warned: "Hudas not Pay"; a traitor is called, "Hudas"; no one is named or baptized "Judas" (although I have baptized children with names like Osama, Bin Laden, Saddam, and Hitler); Our Pasyon scorns Judas as: hayop, palamara, alibughang matakaw, budhi'y salawahan, tampalasan, puno ng kasakiman, lilo.

In retrospect, the issues that will be raised in reading the Gospel of Judas are not something new. Nor they will "shake Christianity to its foundations" as some press releases have suggested. As before, people of faith continue to reflect on these questions.

This makes the Gospel of Judas relevant and interesting to read. As in other ancient literary works, however, critical reading is always prescribed. Here are some tips:

(1) We need to be conscious that what we read is a modern translation of a language that is no longer spoken, and that the manuscript available is one among other copies that got lost or yet to be discovered. The original might no longer be found. Those who had copied the text were working without the technology that we have today like photocopiers and scanners. For sure, they had committed copying errors, and added or deleted some lines, consciously or unconsciously. A good translation depends on a reliable text and a thorough knowledge of the original and target languages, in this case, Coptic and English. That's why a reliable translation of an ancient text must have passed through the rigors of what biblical scholars term as "Textual Criticism". In the case of the Gospel of Judas, this remains to be done. As an example, it was only recently that complete critical editions of the manuscripts discovered between 1947 and 1956 near the Dead Sea in Jerusalem

(2) The circumstances of any discovery of ancient artifacts or manuscripts for this matter are essential to their authenticity. How were they discovered? Usually, an artifact that is found directly from the site by archeologists and not through some antique dealers gains immediately a certain degree of authenticity. The Gospel of Judas is in the possession of a private collector right now. We will wait for the National Geographic issue to tell us the circumstances of its discovery and for the private collector to allow independent experts to examine it. Here's another example to illustrate the warning. Some years ago, there was news of the discovery in Jerusalem

(3) A background literature is needed to understand an ancient text. For the Gospel of Judas, the best background is the Passion Narrative in the four Gospels and the account of the death of Judas in Acts 1:16-20. Paul, the earliest of the Christian writers, was conspicuously silent about the story of Judas. Chronologically, it is proper to read the accounts in the New Testament first before other writings that came later. For Christians, it is wise to remember that the Gospels and the rest of the books of the Bible are sacred writings, the Word of God. Other writings, like the Gospel of Judas, can help us understand the world of the ancestors of our faith, but they are not the Word from whom we draw our joy and hope.

No comments:

Post a Comment